A deep dive into food poverty in the UK

Blog post is available in Welsh here - Ymchwiliad ddwfn i tlodi bwyd yn y DU

Introduction

Since March 2021, we’ve been working alongside Well-Fed, Flintshire County Council and Clwyd Alyn Housing association as well as having regular support from Theatr Clwyd, as part of a project representing the voices and stories of communities in North Wales who are currently, or have experienced food insecurity.

The project has been broken down into a number of stages since original conversations took place last year, and the community outreach portion began March this year. We have spent nearly 3 months engaging with multiple groups across Flintshire and surrounding counties, encouraging open discussion and conversation about stigmas, misconceptions and current social and politic issues. As part of this research period we published a questionnaire on social media with the aim of creating wider image of what knowledge everybody across a broad spectrum of backgrounds has regarding food poverty.

This info pack is in response to that questionnaire. We have collated answers from each question, which will be shown below in the form of graphs and direct quotes and then put together the research that may provide people with further insight into that specific area of the issue. For the majority of questions we have highlighted what we think are the key points for people to take away, but we encourage you to do your own research and engage socially on a wider scale. Throughout this document there is further research, articles, reports etc. linked to not only back up what we are saying but so it is easily accessible for anybody who would like to know more.

Finally, if anything is this info pack sparks a thought, opinion or argument and you would like to talk to us further, please get in touch. We’re always available to chat, either via email or on Facebook/Instagram/Twitter. We’d also love to meet you and hear more about your opinions in person. So get in contact, and let’s discuss!

‘Are you familiar with the term 'food poverty'?’

When asked whether they were familiar with the term ‘food poverty’, 100% of participants responded Yes.

The majority of participants, 62 out of 94, went on to described food poverty as ‘the inability to afford food’. However, many disclosed that they were unsure on how to answer the question.

Below we have defined the term food poverty as well as the broader term of food insecurity.

What is Food Poverty?

Food poverty is the inability of individuals and households to secure an adequate and nutritious diet. Food poverty can affect those who cannot secure food due to economic, geographic or skill-based circumstances.

Many people endure food poverty in the form of hunger. Others do not experience hunger, but do endure malnutrition.

Food Poverty is synonymous with the term Food Insecurity and affects nearly 1 in 3 people globally.

‘The terms ‘Food Poverty’ and ‘Food Insecurity’

Many of the groups we’ve worked directly with during the project prefer the term ‘Food Insecurity’ because it ‘holds more stock’. ‘Food insecurity’ covers a much larger range of issues, from worrying about getting through the month with enough, to not consuming enough nutritious food due to lack of knowledge or skills; from not having access to affordable food options, to being referred to food banks if you find yourself in crisis.

‘Do you believe food poverty exists in your local area?’

88 out of 94 participants believe food poverty exists in their local area. These responses came majority from towns across Flintshire, Denbighshire and Wrexham. With a number of responses from North West Wales and England.

We have found a report from the Institute for Sustainable Food that depicts the percentage adults who experience 3 different areas of food poverty across Wales.

Some form of food poverty exists in every area of the UK.

The University of Sheffield’s Institute for Sustainable Food has created a map, with overlaid shading, to represent data collected from areas in the UK.

They use three layers of shading, in three colours, which depict:

Percentage of adults who are hungry in Wales.

Including those that were hungry but were unable to eat food because they could not afford it, or were unable to access food in the previous month.

Percentage of adults who are struggling to access food in Wales.

Including those who may have sought help within the last month with access to food, have cut back on meals and healthy foods to stretch tight budgets, or indicated that they struggled to access food in some way. In some places the rate is as high as 28% of adults.

Percentage of adults who worry about food insecurity in Wales.

Or being able to continue to supply adequate food for their household. These people may be just about managing but could slip into food insecurity as a result of an unexpected crisis, or sudden lack of funds that is usually allocated towards purchasing/ procuring food.

The interactive map is available here

‘How many people, on average, do you think require food support at the moment?’

35 out of 94 participants believe that 43% of people require food support currently, which coincides with the previous question where most people are aware of it being prevalent in their area.

Interestingly, 2 participants believe the number to be closer to 25% as this is the percentage for number of children in Wales who currently receive free school meals.

Official reports put the number at approx. 10% of the population being in need of support. However, many organisations believe Government data to be incorrect. You can read more about this below.

According to Hungry for Change: fixing the failures in food, a report published in June 2021 by the Select Committee on Food, Poverty, Health and the Environment, “The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN estimated that around 2.2 million people in the UK are severely food insecure (i.e. with limited access to food, due to a lack of money or other resources). Until recently, however, the Government has not collected data on this and so does not have an accurate picture of the prevalence of food insecurity”

Notice the use of the word ‘severely’. As Sheffield’s Institute for Sustainable Food points out, there are nuanced and varied experiences of those facing hunger, which is not limited to those who face ‘severe food insecurity’. We must include those who are worried, struggling, or who often, or sporadically, find they do not have enough.

It is right, however, that because the government has not collected data, we cannot have an accurate picture of UK hunger.

However, there is more data collected by The Food Foundation that estimates people enduring food poverty in the UK in 2022 is 8.8%. Which would accumulate to 5.93 million people (including 4.7 million adults). [Source]

We assume this is closer to the real total, but still incorrect. Many people we, and our partner organisations, have spoken to have covertly admitted to having endured food insecurity, but would never have used the phrase, or have ever sought help.

How could these people’s experience be included in official estimates?

The CEO of Well-Fed, our partner organisation, Robbie Davison has been working in food poverty for over a decade. Robbie works directly on the ground with people struggling, writes about his thoughts, and takes his findings to parliament.

His estimate is that the total number of people who are enduring / will have endured food poverty within the last year is more than the combined population of Wales and Scotland. [Source]

If we use his estimation, we can calculate:

The current population of Wales is 3.19 million.

The current population of Scotland is 5.51 million.

Together that’s 8.7 million.

The Population of the UK is 68.5 million.

(68.5 / 8.7) x 100 = 12.7

12.7% = (approximately) 8.69 million people enduring food insecurity

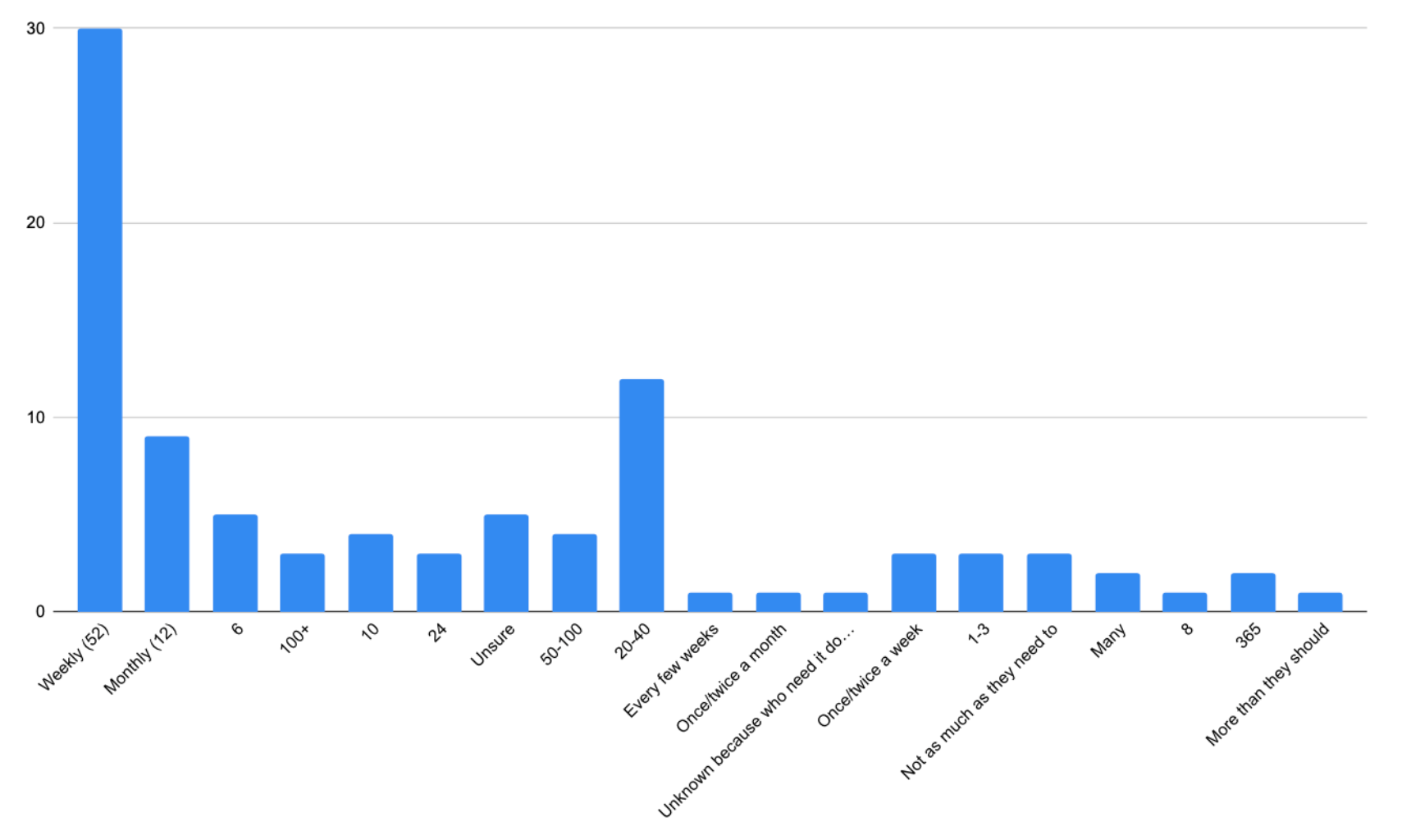

‘How many times do you think a person struggling with food access uses a food bank within a year?’

A large proportion of participants believe that a person can access a food bank weekly/52 times a year, however the reality is far from that.

UK citizens can access a food bank 3 times within a 6 month period, therefore 6 times annually.

Many people we’ve worked with have been shocked to learn this. And while we understand that there are cases where people are able to access support when they need it, the guidelines state that there is a limit on the number of referrals a person can receive.

To attend a food bank, a person must be referred by a professional person such as;

a social worker

Citizens Advice officer

a councillor

a civil servant

a GP

and they must meet certain standards to receive that referral. [Source / further reading] Do you think that this is sufficient to work towards combating food insecurity?

‘What more do you think could be done, by either government, local bodies, or community organisations?’

There were many detailed responses to this question, and we have collated them into general categories for the purposes of analysing responses. The most popular suggestion is that better UC/benefit/employment options are needed. The 3 highest responses after this include;

higher taxation on wealthier members of society and lower public tax.

education and awareness of changes in lifestyle and peoples approach to food.

increased funding for food banks and other food support options.

There is a good mixture of responses that range from education to funding to considering the individual. And while the ‘correct’ solution is up for debate, we have outlined below what it could look like for the Government to support some of those initiatives, and what more they could be doing that they currently aren’t.

Reasonable Government intervention could look like:

Up-skilling:

A call by the Select Committee on Food, Poverty, Health and the Environment notes that the government should be aiming to produce clear public health messaging as well as reforming public food measures such as Healthy Start vouchers, free school meals and holiday hunger programmes.

They also believe schools and local authorities play an important role in educating citizens on skills relating to nutrition, noting that such authorities must be adequately resourced in order to do so. [Source]

Additionally, Government Social Spending could fund third sector services to better educate citizens on skills like budgeting, cooking, nutrition and other educational courses that allow citizens to have more agency.

Research and information-collection:

Many people we’ve connected with have suggested there must be a way for governments, councils and local authorities to collect data from the public about their situation, to get a better grasp on how many people are experiencing food poverty - and how severely.

This data collection could be done by way of a survey completed by all citizens, similarly to the census. Alternatively, the Taiwanese government has implemented an app/ internet-based system where they collect data and incentivise citizens to vote on aspects of legislation, at weekly intervals.

The UK could fund similar projects to incentivise the public to be more abreast of, and involved in, policy-making and democratic decisions, as well as collecting data about individual circumstances. [Source 1 / source 2 / source 3]

Welfare and social spending:

In order to ‘adequately resource’ these authorities, governments must increase social spending. The highest rates of social spending are in Norway where the rates of suicide due to job-loss are the lowest globally, because a decent welfare safety net exists. [Source]

We do not believe in Cash-First welfare schemes without other basic needs for people being met. If recipients of universal credit need to choose between spending their money on rent, bills, other expenses and food, they will still rely on emergency food services which aren’t fit for purpose. [Source]

Universal Basic Income (UBI), an initiative to give all citizens of a country money at no cost to the receiver (no matter their other income). In the UK £40-60 monthly payments have been proposed. UBI could ensure that all UK citizens receive at least enough to guarantee a basic standard of living. [source + further reading] A criticism of this is that it would be expensive and would include allocating money to those who are already experiencing high standards of living. Wales is beginning a scheme where a trial-size group of 500 citizens will receive £19,200 yearly, or £1,600 monthly, for the next three years. The citizens enrolled in the trial are care-leavers of around 18-25 years old. [Source / further reading]

The New Economics Foundation has posited that UBI could be implemented by ‘putting everyone in the country on universal credit’, effectively topping up any citizen’s income if it fell beneath a certain standard. Citizens then would not need to jump through bureaucratic hoops in order to receive welfare. They would also not have to wait 6 weeks to enrol. [Source]

If not UBI, we might implement a multiplicity of welfare/benefits schemes, rather than a standardised Universal Credit program. Ensuring that people have access to decent welfare which is fit for their individual needs - and which covers their individual lifestyles and (unpaid) labours.

Food and fuel vouchers rather than simple cash, automatically allocating portions of welfare to be spent on food, in case of situations where persons are unable to budget effectively. (However, each of these suggestions should come in tandem with other social spending schemes to increase knowledge, ability and skills, in order to create sustainable change.)

Removal of the 6-week waiting list for welfare to reduce the amount of people who have to take out loans during that period, falling into a cycle of endless debt.

How might we fund this? ‘Tax the rich’ - the Patriotic Millionaires, a group of high net-worth individults have built an organisation encouraging the UK and US governments to tax the upper classes more highly than its lower and middle earners. “Don't tax the poor and the middle classes so heavily. Tax us instead.”

Some steps the government has taken EVALUATED:

A national minimum wage increase (from £8.36 to £9.18 for those ages 21-22 and from £8.91 to £9.50 for those aged 23+) was put into effect on April 1st 2022.

The Soft Drinks Industry Levy (sugary drinks tax), reducing unhealthy sugar consumption and providing funds to pay for school breakfast clubs (when costs of something people usually buy is increased, your general outgoings are increased, no matter what it is on. We want to increase choice and diversity in people's diets regularly - putting an extra tax on something someone perceives as a treat isn’t helping - it just adds extra costs.) (Breakfast clubs work in the same way as charities, in that it’s a plaster over a problem caused by lack of government funding.)

Protection of children from junk food advertising and marketing (just eat and deliveroo still marketed everywhere. Do we really think children see no junk food advertisements?)

A recent promise to fund pilots of projects tackling holiday hunger for children living in low-income households (with thanks to Marcus Rashford for bringing this issue into the limelight, and taking it to parliament. 321 Members of Parliament voted against the motion to give children meals through holidays. 261 voted in FAVOUR of it. You can view the figures here.)

Many of the steps taken by the government to reduce obesity and encourage healthy eating have failed and, according to the Select Committee on Food, Poverty, Health and the Environment, these figures have actually continued to rise. [Source / further reading]

‘Please describe the kind of person you believe lives in food poverty’ / Who is affected by food poverty?’

We included this question to gauge whether the publics perception of what people who live in food poverty are like matches up with the statistics of group within society who are most likely to experience food poverty.

37 participants stated that anyone could be living in/affected by food poverty. With those living in low income areas, families on benefits and those who are unemployed, being the next most popular responses.

None of these answers are the ‘right one’ as technically there is no ‘right answer’ for who can experience food poverty. However, food poverty, including less-healthy diets and access to adequate food and resources, is not limited to those in the lowest income groups, but these groups are affected disproportionately.

Adults, children and the elderly living in more deprived areas are significantly more likely to become obese or suffer with diet-related ill health. Health inequalities in the UK have widened as a result of this.

Geographical location can affect people's access to affordable, varied and nutritious food. Many people living in rural areas may not have access to bigger supermarkets, market stalls, community pantries, food banks or any of the other places many of us aquire our food. [Source / further reading]

This year, people living with disabilities are approximately 5 times more likely to experience food insecurity than people who aren’t. [Source / further reading]

'Do you associate the term 'free school meals' with food poverty?'

46.2% of participants said that Yes they did associate free school meals with people living in poverty. With a number of these responses coming from personal experiences and definitions of criteria for who is edible. Those who answered No had similar reasons as well as many stating that they shouldn’t be associated with poverty as school meals should be free to all children.

While meeting the criteria for free school meals, doesn’t directly correlate with being in poverty, at this point in time, there are many families who rely on their children receiving their main hot meal of the day, for free in school, as it takes the strain off food purchases. And this could mean that they are able to stay out of poverty.

Child poverty has significantly risen by 500,000 since 2021, from 3.6 million children, to 4.1 million. Alison Garnham, Chief Executive of the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) expects this figure to rise to above 5 million by the end of 2022.

The figure for in-work poverty has also risen at a similarly significant rate.

7 out of 10 children living in poverty live with at least one parent who is in-work.

If parents are in-work, their children may not be entitled to support like free school meals, which are based on receipt of benefits. [Source / further reading]

Wales is planning to prepare the infrastructure for all primary-age children to be entitled to free school meals by 2024. [Source / further reading]

If children are able to access free school meals, they’re fine when they’re in school, but what happens when they’re not in school? A recent promise to fund pilots of projects tackling holiday hunger for children living in low-income households (with thanks to Marcus Rashford for bringing this issue into the limelight, and taking it to parliament. 321 Members of Parliament voted against the motion to give children meals through holidays. 261 voted in FAVOUR of it. 64 Members were absent for the vote. You can view the figures here.)

Why is fixing the broken food system important?

‘The health of the population, and the health of the planet, is at risk.’ Billions are spent each year by the NHS treating significant, but avoidable, levels of diet-related obesity and non-communicable diseases (heart diseases, cancers, diabetes, kidney disease etc). Diet-related illness affects all sections of the population, but it affects deprived areas considerably more, effectively creating/ maintaining/ steepening health inequalities.

‘The gradient in healthy life expectancy is steeper than that of life expectancy. It means that people in more deprived areas spend more of their shorter lives in ill health than those in less deprived areas.’ [Source]

Food retailers, large food commodity companies, manufacturers, and the food services sector, perpetuate the demand for highly processed, less-healthy products. Not only does this directly impact public health, but negatively impacts efforts to produce food in an environmentally sustainable way. Demands on farmers to produce food cheaply effectively threatens biodiversity and the quality of farmland. [Source]